When people imagine the ancient Greeks they often picture white marble statues, flowing robes, and sunlit columns. Yet behind those images lies a rich, practical, and symbolic world of clothing and appearance. This article explores the subject of fashion in ancient Greek societies, tracing how garments were made, who wore them, what they meant, and how they shaped daily life, identity, and status. I will write in clear, accessible language so anyone can follow, and I will weave historical detail with cultural context so the reader gains both a concrete and human understanding of ancient dress.

What “fashion in ancient greek” really means

The phrase fashion in ancient Greek can mislead if taken to mean rapid trends like those today. Clothing in ancient Greece combined long-lived styles with local variation and social signals. Garments were typically simple in cut but varied widely through fabric, color, draping, ornament, and the ways people wrapped and fastened cloth. While the basic items—like the chiton, himation, and peplos—remained recognizably similar for centuries, innovations in weaving, dyeing, and tailoring created differences between city-states, classes, and occasions. The simplest way to think about ancient Greek fashion is as a language of fabrics and forms that communicated age, gender, profession, wealth, and ritual belonging.

Common garments and how they were worn

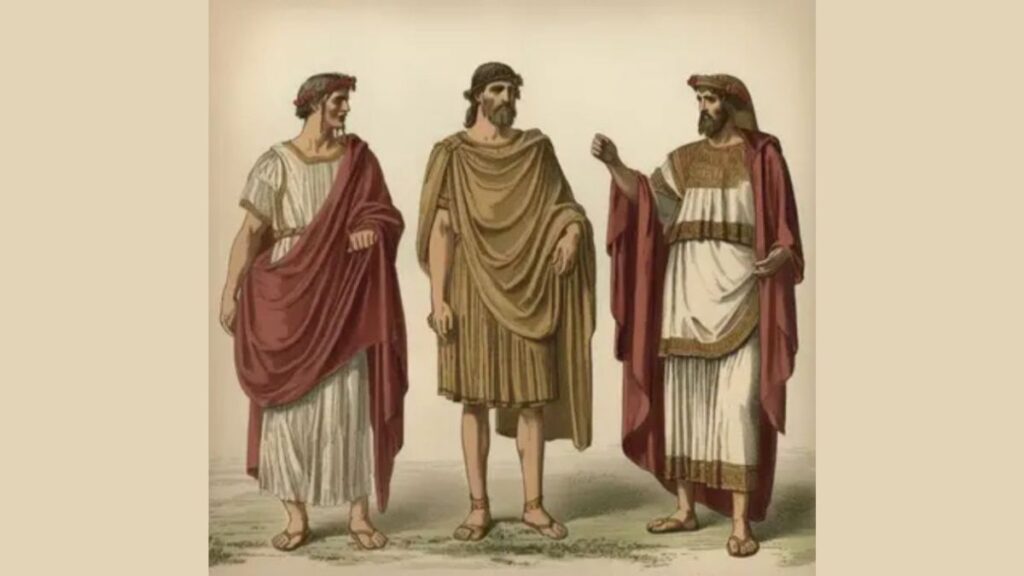

One of the most famous garments was the chiton, a rectangular piece of linen or wool folded and sewn or pinned at the shoulders, then belted at the waist. Men often wore shorter chitons for work and longer ones for formal occasions. Women wore longer chitons, sometimes doubled over or gathered to create a fuller, graceful appearance. The peplos was a distinct garment for women in many city-states, a heavier woolen cloth fashioned into a tube and pinned at the shoulder so the upper part folded over, creating a distinctive layered look. Over either the chiton or peplos, Greeks might drape a himation, a cloak-like wrap that offered warmth and formality. The himation could be worn over both shoulders or slung over one in a way that signaled casualness or sobriety.

Clothing choices were shaped by climate, work, and social expectations. A farmer’s practical short chiton allowed movement, while a philosopher’s himation might be wrapped in a way that suggested study and restraint. Fabrics mattered: linen from flax was lighter and preferred in hot summers, while wool kept people warm in winter. The way a cloak was folded, the width of a belt, or the presence of fringe and embroidery could all communicate subtle social information.

Accessories, footwear, and grooming

Shoes varied from simple sandals to more enclosed boots for travel. Jewelry, especially pins and brooches used to fasten garments, served both functional and decorative roles. Women often wore ornaments of gold, beads, and precious stones, and hair was styled and dressed with combs and ribbons according to age and occasion. Men kept beards for long periods, but shaving and haircuts could also follow fashions of different periods. Cosmetics and perfumes were used, particularly in urban centers, as part of daily grooming and ritual practice.

Materials, weaving, and color

Textiles were the backbone of clothing. Spinning and weaving were common crafts in many households, and the quality of cloth could vary from coarse homespun to fine, tightly woven fabrics imported from distant regions. Wool was the most common fiber, grown locally and prepared at home, while linen required flax and more labor in production. For wealthier households, exotic imports such as silk arrived later and became prized.

Color played a major role in appearance. Natural dyes produced beige, brown, and ochre tones, while more skilled dyers could achieve bright reds, deep blues, and rich purples. Purple dye, derived from certain shellfish, became a prestigious marker of nobility and wealth in later periods because it was costly to produce. Colors could indicate status or affiliation: certain hues might be associated with specific rituals or professions. Patterns were created through complex weaving techniques or embroidery, and patterned fabrics signaled both craftsmanship and taste.

Regional and social variation

Ancient Greece was not a single, unchanging culture but a mosaic of city-states, islands, and mainland regions. Clothing reflected that variety. Athenians, Spartans, Corinthians, and island communities all had local preferences. In Sparta, for instance, clothing could be plain and austere as part of a cultural ethic that prized simplicity and communal discipline. In contrast, coastal trading cities with wealthy merchants might display exotic fabrics and elaborate ornamentation.

Class distinctions were also visible in dress. Wealthy citizens could afford finer materials, dyed textiles, and decorative metalwork. Slaves and laborers wore simpler garments suited to work, and their dress often revealed their social position. However, clothing could be changed; a freed person who acquired wealth might wear better fabrics and adopt elite styles. Ritual and gender norms influenced clothing strongly: priests and priestesses had ceremonial garments for rituals, and gendered expectations guided how men and women layered and fastened garments.

Clothing and identity: gender, age, and profession

Clothing communicated identity as clearly as language did. Men’s roles—citizen, soldier, artisan—came with typical styles that balanced practicality and social signaling. Soldiers wore armor over garments and often attached symbols to their clothing or shields that marked city loyalty. Women’s dress emphasized modesty and marital status in many places; married women often wore veils or additional wraps in public to indicate their status. Children’s clothing changed as they grew; boys might switch to male attire at a certain age marking civic coming-of-age rituals.

Profession also shaped appearance. Priests and ritual specialists wore garments suitable to sacred duties, sometimes embroidered with religious symbols. Athletes competing in public games were often nude, which itself was a cultural fashion of masculinity in many Greek contexts. Philosophers and intellectuals could adopt simpler clothing as a mark of philosophical seriousness, which in some cases became an enduring fashion within particular schools.

How garments were made and who made them

Making clothes was labor-intensive. Spinning, weaving, dyeing, and tailoring involved many skilled hands. In many households, women were central to textile production, spinning yarn and weaving on looms. Specialized workshops and professional weavers existed in cities, and some garments, particularly elaborate ceremonial robes, were produced by artisans who specialized in embroidery and decoration. The economic life of textiles was important: textile production could be a household industry but also a commercial sector that connected local economies to broader Mediterranean trade.

Practical care and repair

Clothes were valuable and often repaired rather than discarded. Mending extended the life of garments, and households developed skills in darning and patching. Washing and care required water and soap-like substances, and garments were aired and brushed to maintain cleanliness. The persistence of classic garment types across centuries was partly practical: rectangular pieces of cloth are easy to cut, adapt, and mend, so the basic style endured while surface decorations and accessories changed.

Legacy and influence on later fashion

The aesthetic of ancient Greek dress—drapery, plain lines, emphasis on form and movement—has inspired artists and designers for millennia. During the Renaissance, neoclassical revival in the 18th and 19th centuries, and again in modern haute couture, designers have borrowed Greek silhouettes and draping techniques. Sculptors and painters who study ancient artifacts help modern audiences imagine how garments once looked in motion, and museums preserve textiles, pins, and frescos that give direct evidence. The visual language developed by the Greeks, where fabric reveals the human form rather than hides it, remains a powerful influence on modern ideas about style and artistry.

Table: Quick reference of common garments

| Garment | Typical wearer | Material examples | Social or functional notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chiton | Men and women | Linen, wool | Versatile; length and width indicate formality |

| Peplos | Women | Wool | Often worn by married women; folded over at top |

| Himation | Men and women | Wool, linen | Cloak-like; used for warmth and status display |

| Chlamys | Men (traveler, soldier) | Wool | Short cloak fastened at shoulder for mobility |

| Exomis | Working men | Coarser wool | Practical for labor and movement |

Lists expressed in narrative form

First, everyday dress was designed for comfort and climate, so people chose lighter linen in summer and heavier wool in winter. Second, ceremonial dress prioritized symbolism and craft, with embroideries, dyed panels, and special fastenings reserved for religious rites, weddings, and political events. Third, changes in fashion were often slow and localized rather than sudden and global; innovations such as refined dyeing or imported fabrics arrived through trade and gradually affected aesthetic choices.

How to read visual evidence today

Archaeologists and historians rely on surviving textiles, metal pins, frescoes, pottery, and sculpture to reconstruct dress. Statues carved in marble freeze a moment of drapery and posture, while painted pottery can show everyday scenes of athletes, markets, and weddings where garments appear in use. Textual sources—poems, plays, and manuals—describe clothing, sometimes with technical detail. By reading these sources together, scholars build a layered picture of how items were made, worn, and perceived.

Conclusion

Fashion in ancient Greek societies was more than decoration; it was a system of expression grounded in material realities, social expectations, and moral values. From the practical chiton of the farmer to the richly dyed robes of the elite and the symbolic garments of ritual specialists, clothing helped ancient Greeks present and understand themselves. By studying garments, dyes, and surviving images, we learn how a seemingly simple rectangular cloth could become a complex language of identity, community, and beauty. Whether you study history, design clothes, or simply enjoy imagining the past, the story of ancient Greek dress offers both practical lessons and lasting inspiration.

Frequently asked questions

What is the difference between a chiton and a peplos?

The chiton is typically a sewn or pinned garment worn by both sexes and adjustable in length, while the peplos is a heavier, often woolen garment primarily for women, characterized by a top fold that creates a layered look.

What is the significance of color in ancient Greek dress?

Color signaled wealth, affiliation, and sometimes ritual meaning. Bright and costly dyes were markers of status, while simpler hues were common for everyday wear.

What is a himation and when was it used?

A himation is a large cloak wrapped around the body, used over other garments for warmth and formality, and worn by both men and women in various social contexts.

What is known about male and female grooming?

Both men and women cared for hair and used oils, combs, and perfumes. Hairstyles and the use of beards changed over time and could reflect philosophical or regional identities.

What is the evidence for ancient Greek textiles?

Evidence comes from surviving textile fragments, tools like spindles and loom weights, depictions on pottery and sculpture, and descriptions in literature and inscriptions.

What is the modern relevance of these garments?

Modern designers and artists continue to draw inspiration from Greek drapery and simple silhouettes; understanding these garments illuminates continuity in human aesthetic and practical needs.